Three

telltale “remnants” or projections on the casting that can be used as

part of

the authentication process for medium and larger solid shot.

By

David Poche with Peter George

Terminology: Solid

Shot are spherical solid (not hollow) cast iron objects that are fired

from

Civil War cannons.

The Problem of Identification: Unless you have personal knowledge of an excavated solid shot from a Civil War location, the authenticity of the object is subject to interpretation. Typically, spherical cast-iron or steel balls are purchased at garage sales, auctions, antique shops, or on Ebay. Sometimes individuals state a provenance for the object like “my grand-pappy plowed this up on his farm”. Shot of this type can come in all sizes and are usually made of steel, cast-iron or brass. Civil War cannonballs were never made of steel or brass. Many non-authentic items at these events turn out to be large ball bearings, cement truck tank cleaning balls, roller mill balls, wrought iron ornamental fence balls, and even old high school Sports shot puts. Each of these items has a telltale set of characteristics that can point us away from being non-authentic.

Cast

Iron Versus Steel: Authentic cannon balls

and

smaller solid

shot (canister and grape) are made of cast-iron rather than steel. The Federal

Ordnance Manual of 1862 stated that all shot and shell were

to be

fabricated from cast-iron with only one exception (lead).

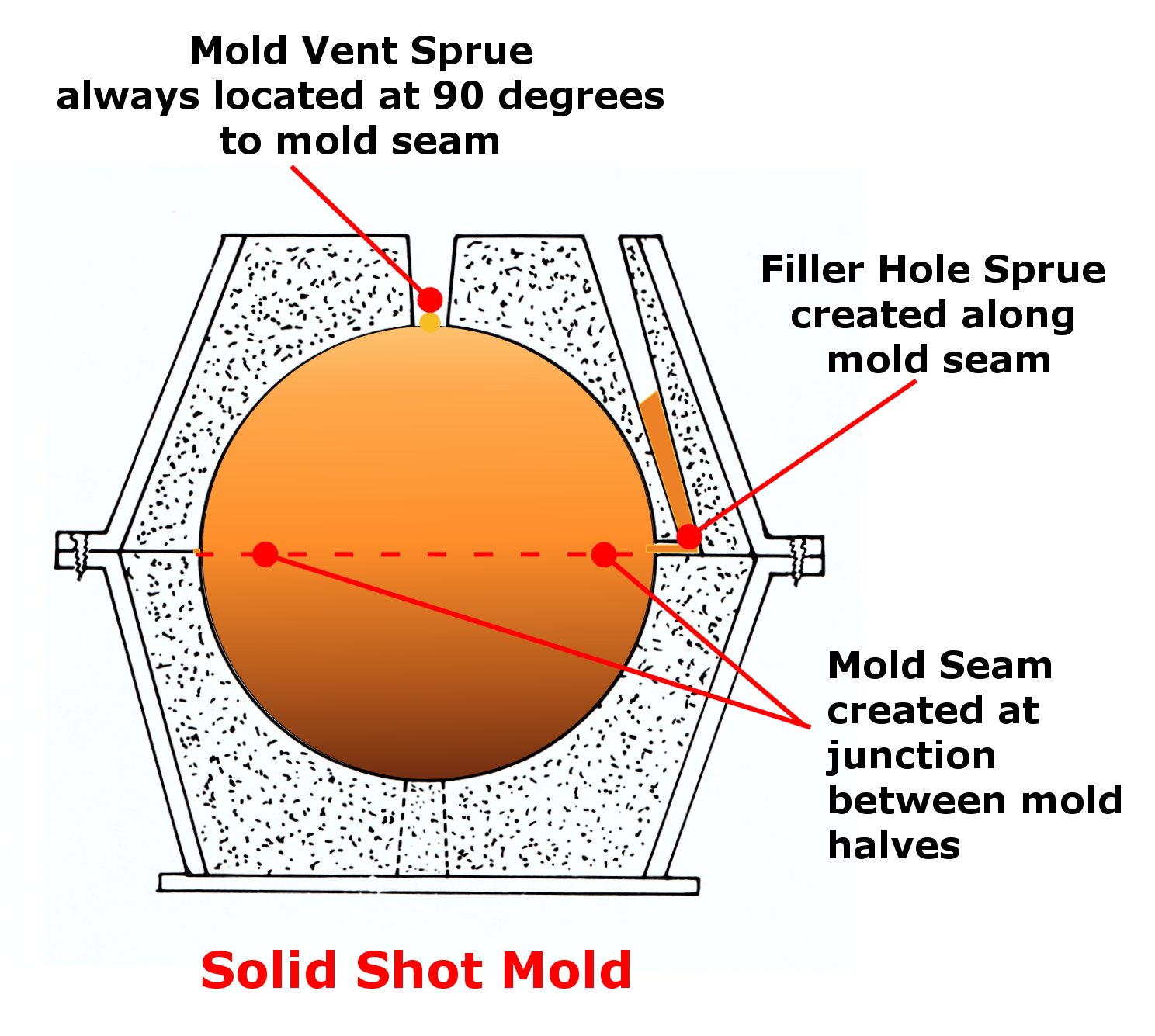

How are they cast?

The

casting of solid shot and shell is well covered in

Dean Thomas’ book Cannons.

Basically, two hemispherical

sand molds are prepared and are attached together. The mold-pair is

filled from

the side at the seam between the two mold halves until liquid cast iron

appears

in the mold’s vent at the top.

The

casting process creates three distinct telltale

identification points on cast solid shot that point to authenticity.

These

are:

(1)

The mold

seam created by liquid metal flowage into the tiny gap

between the two mold

halves;

(2)

The filler

hole sprue created at the mold seam from liquid metal

entering the mold;

(3) The mold

vent sprue created as the metal begins to fill the hole at

the top of the

mold. The vent sprue is always at a right angle to the plane of the

mold seam.

The

filler hole sprue is always located along the mold seam on

cannonballs and is usually represented on the finished product as a

small (0.25

to 0.50 inch) imperfection. If the cooling of the metal of the casting

caused

the metal in the vent to contract and create a depression in the

casting this

was sometimes patched with lead (rare).

Inherent

in this type of casting is the presence of air bubbles

being trapped inside the casting. This has the effect of

weight reduction of

the casting.

Three

telltale “remnants” or projections on the casting that can be used as

part of

the authentication process for medium and larger solid shot.

After

casting,

any metal surface projections on the solid shot were removed by hammer,

chisel,

and file. Special care was taken with cannonballs since any projections

would

be likely to come in contact with the cannon’s bore and would or could

damage

the bore due to metal-to-metal scraping. Poorly cast (cannonballs with

surface

projections) could also jam in the bore causing the barrel to burst on

firing.

This

is why

cannonballs were manufactured to be perfect spheres and never

out-of-round

(like an egg, potato, or onion).

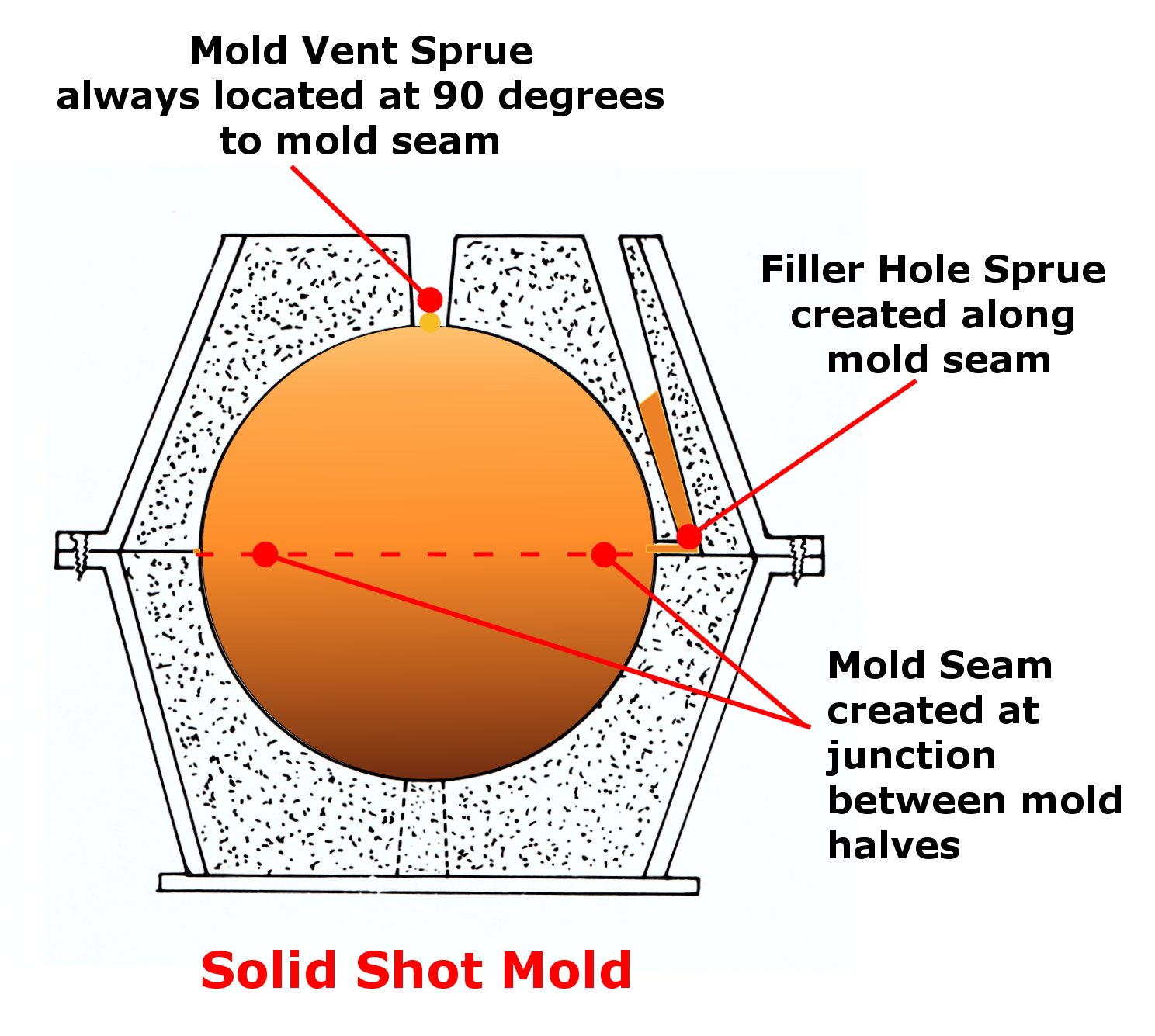

At

the

smaller

end of the caliber spectrum of solid shot, surface projections are more

apparent. Canister might display some finishing. Also canister mold

seams,

casting and vent sprues will be more apparent than on larger caliber

solid

shot.

Much

less care

for removing casting remnants was taken for grape shot and canister

since these

projectiles have little contact with the cannon’s bore during firing.

Knowledge

of solid

shot casting will bear directly on the types and location of

measurements made

on solid shot for authentication.

Smaller

solid shot was Gang-cast, in which multiple canister or

grape shot were cast in a single mold. These shot would all have a mold

seam

line but would vary in the type of sprue projections present, depending

upon

the type of gang mold used. Some gang molds had interconnected flow

channels;

others did not. Thus the castings of canister and case shot frequently

have

some surface casting projections and are usually much “rougher”.

Smooth Surface of a 4.52 inch (actual diameter) 12 Pdr. caliber cannonball showing only a very faint trace of a mold seam.

Note the rough and irregular nature of the surface of these Gang-cast canister balls. They may or may not have been tumbled in a milling barrel to remove their casting projections as required by the Ordnance Manual. Expeditious shortcuts in manufacturing were often taken during the Civil War. Steel ball bearings (non-authentic) of this size will have no such casting projections. The gang-cast canister balls in the photo were excavated by the author Poche at Port Republic, Virginia.

There

is a

simple three-step method for determining the

authenticity of solid shot. This method plus a few caveats will

significantly

enhance your odds of purchasing authentic pieces.

Step One: Determine the

Diameter of the Ball

Three tools for measuring the diameter of solid shot: the diameter tape, the machinist’s feeler gage and the electronic caliper.

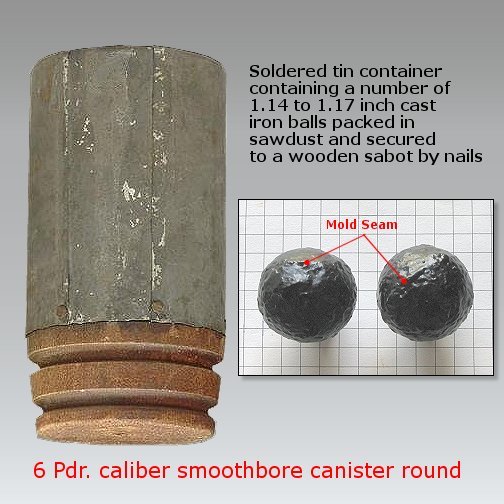

For

large cannonballs, place the ball so that the plane of the

mold seam (“equator”) is vertical and the “poles” are horizontal.

Measure with

a mechanist’s feeler gage or calipers slightly off the poles along the

opposite

red arrow lines shown in the figure below.

Measurement

locations

for the

diameter of “possible”

cannonballs. Measurement should be made with calipers or a machinist’s

feeler

gage in the plane of the “Pole” and using the opposite red arrow lines.

CAUTION: Avoid making measurements at the poles since casting

projections could

disrupt diameter measurements.

There

might be a casting projection at the pole location. Slide

the feeler gage or calipers up and down to make sure that the maximum

diameter

(thickest point) is being measured. Take the largest measurement and

lay

measure against ruler with 10ths of an inch or read the calipers

directly.

A

casting filler sprue (if any) would be located along the mold

seam and the vent sprue, if present, would always be located at the

“pole” (90

degrees away from the mold seam). These will surely be present on

smaller solid

shot (canister).

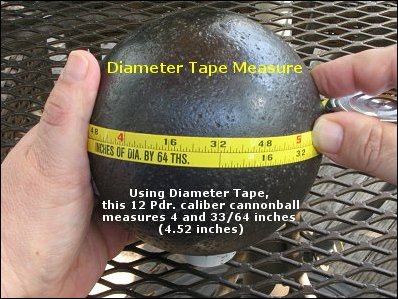

Another

method for measuring the diameter of larger solid shot

is to use a diameter tape (like Stanley model

33-115 -available from

most hardware stores). This tape is wrapped around the “equator” of the

ball

and its diameter can be directly read from the backside of the tape.

An

easy way to measure

the diameter

of cannonballs is to

use a diameter tape, which measures the diameter of the ball directly.

Surface Examination:

Any large

surface irregularities or pronounced out-of-roundness suggests that the

object

is non-authentic.

The

general surface of a cannonball should be smooth unless

heavily pitted by corrosion. There should be no wide belts or

raised bands

at the mold seam, but a faint trace of the mold seam (if any) as the

previous

picture of the 12 Pdr. shows. There should be no

flat spots, egg-shape

or out-of-roundness to the object.

If

surface projections or dimples are present, but not in their

correct places (pole and equator), then this points to the object as

being

non-authentic.

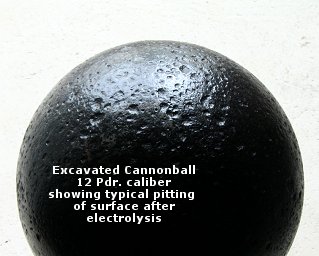

Surface pitting of excavated solid shot is to be expected due to the migration of elemental iron to a new location on the surface of the ball where rust scale (iron oxide) is formed. Excessive scale may influence diameter measurements.

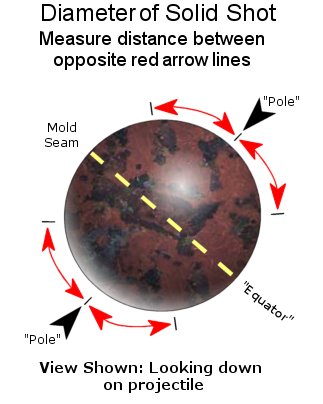

Smaller

diameter solid shot (such as grape shot, and canister

shot) often tends to be more irregular than midrange-sized cannonballs.

Expect

fairly pronounced mold seams and clear evidence of the locations of

removed

filler and vent sprues. These former casting projections are located at

the

same points on the surface of the sphere as larger solid shot. Because

many of

these projectiles were gang cast, they will only have filler sprues

along the

mold seam. In

Gang-casting, a mold vent

was present only in the last projectile of the Gang-cast line.

Manufacturing

tolerances of grape shot and canister were not

nearly so precise as those of cannon balls since they were not intended

to come

into continuous contact with the cannon’s bore. Generally armories

and their subcontractors were allowed plus or minus 0.03 inches on the

diameter

of the smaller caliber solid shot they produced.

The

measured values of diameter will be compared with ranges

given in the Shot

Tables of the Ordnance Manual of 1862. Excavated

cannonball measured

values must fall within the range of the Tables to be considered

authentic.

Caveat: The

diameter of any solid

shot may be

altered by the effects of pitting or scaling of its surface, and

exposure to

acidic ground water. Both effects may make it lighter.

It

should be pointed out here that with only one exception, no

military solid shot was ever fabricated at a diameter equal to a ruler

fraction

(1/4,

½,

¾ or an

even 1).

Ruler-fractioned objects are all civilian rather than military and a

quick

glance back at the Shot Table diameters will confirm this. The single

exception

is the 32 Pdr. caliber cannonball, whose specified diameter was 6.25

inches. If

an iron ball is encountered that has a diameter equal to a ruler

fraction, like

3 and ½ inches (3.50) then it is not authentic.

Stamp Marks: Most

authentic Civil War cannonballs have no stamped numbers or letters on

them. Old

sports Shot Puts frequently have the numbers: 6, 8, 12 or 16 stamped on

them or

their metric weight equivalent for more modern Puts. These stamps

represent

their sports weight classification.

Peter

George says he has seen only one specimen with a low

number like “2”. Some cannonballs had a Arsenal Inspector’s mark, which

was a

single letter like “G” (Selma Arsenal) on solid shot. He says this is

extremely

rare. Thus we can probably say any number “6” or greater stamped on an

iron

ball is probably a sports Shot Put or a machinery counterweight, and

not a

solid cannonball. Multiple-stamped letters on solid balls are even

rarer and

also indicate the non-authenticity.

Step Two: Determine the Weight of the Ball

The

second step

in authentication is to use a digital scale to obtain the weight of the

solid

shot with high precision. Bathroom scales are notoriously bad at giving

correct

weight. Grocery stores also may let you weigh a small shot. CAUTION:

Be

sure to check the maximum weight capacity of any digital scale you use.

The

maximum capacity is usually written on the front of the scale.

Caveats: Often,

steel balls are sold as solid shot. Steel is denser that cast iron. For

the

same exact size of ball, a steel one will weigh

some what more than cast iron one.

Also

when comparing with the Ordnance Manual’s specified

weights for cast iron shot, remember that cast iron molding inherently

creates

bubbles inside the casting. Internal casting bubbles will make the

solid shot

lighter.

Authentic

cast iron solid shot may be lighter than the

Ordnance Manual Shot Table weight but it can never be heavier.

If a

particular shot has the correct diameter but is heavier than the weight

listed

in the Shot Tables, then it is probably steel.

The weight of a military solid shot

is never specified to

be an even

pound. If

an iron

ball is encountered with an even pound weight,

such as 3.0 or 4.0 pounds then it is not authentic and points to

civilian. The

exceptions to this rule are 8 inch and

larger caliber solid shot, but that is because the Ordnance Department

was not

concerned with specifying ounces at such great weights (65 pounds and

up).

Step Three: Match the

Measurements to the Ordnance

Manual Shot Tables

The

last step in the authentication procedure is to match a

ball’s weight and diameter with those published in the Ordnance

Manual (1862 ) Shot Tables

or in Jack

Melton and Lawrence

Pawl’s Artillery Website.

The

Manual’s tables of weight and diameter of all solid shot

(cannonballs, canister shot and grape shot) are considered to be the

accepted

value for authenticity. Compare your values of diameter and weight to

the

values found in the tables.

A Non-Authentic Example:

The

figure below shows a classic non-authentic ball actually put up for

sale at a

recent Civil War Relic Show. It appears to be about the correct size

for a 12

Pdr. caliber cannonball, but it is not of Civil War vintage nor even a

military

cannonball. The

metal of the ball is

somewhat shiny; this points to steel rather than cast iron. Excavated

cast iron

will always have rust and visible pitting while excavated steel will

have much

less rust and little or no pitting.

The

flat countersunk screw also points to non-authenticity.

This screw could cover a filler hole for a Shot Put, or it could be

covering a

point of attachment of the ball to a larger structure like a fence or

gatepost.

None of these characteristics point to an authentic piece.

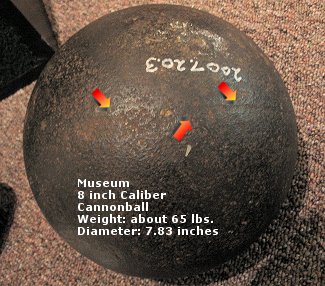

As the caliber of solid shot increases, the amount of apparent final metal finishing decreases. Shown above is an 8-inch caliber cannonball in a museum with no apparent casting sprues and a very faint mold seam as indicated by the arrows. There are no “wide” band mold seams on authentic solid shot.

The

Ordnance Manual required that all shot

and shell be inspected both upon delivery from the manufacturer as well

as

periodically. When ordnance inspectors checked the diameter of solid

shot and

shell they used two sets of handheld metal ring-gages like the one

shown below.

The

watchwords at any public sale should be “caveat emptor”

even at Relic Shows. A few simple measurements and observations can

save the

purchaser a lot of money.

Still in Doubt? Get in Touch with

a Civil War Artillery Expert: If in doubt

about the authenticity

of any solid shot you are about to purchase, it is best to contact a

helpful

Civil War local artillery expert.

Author

Poche’s Note:

Almost

the entire above article is based upon discussions with Civil War

artillery

expert Peter George and author Poche is indebted to him for his

tireless

efforts to train the author in this subject. Without his knowledge,

this

article could not have been written.

Good

Additional

Readings:

Dean

S. Thomas, “Cannons:

An Introduction to Civil War Artillery”; 1985; (ISBN 9780939631032); 72 pp.

United

States Army Ordnance

Depot, “The Ordnance Manual for the Use of Officers of the

United States

Army”; 1862 & reprinted 2006; University of Michigan

Library

Reprint; (ISBN

9781425559717); 540 pp.

Also available through Google

Books.

Dickey,

Thomas S. &

George, Peter C., “Field Artillery Projectiles of the American

Civil War”;

1993; Arsenal Publications II; (ISBN 0960902201); 552 pp.

US

War Department, “Instruction

for Heavy Artillery”; 1851, 270 pp. Also available through Google

Books.

US

War Department, W.H.

French; W. F. Berry and H.J. Hunt “Instruction for Field

Artillery”;

1863, 281 pp. Also available through Google

Books.

John Gibbon, “The Artillerist’s Manual”; 1860; (ISBN 1402114230); 568 pp. Also available through Google Books.